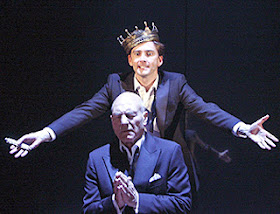

Yes, it's time again for the Shakespeare in the News roundup. Tonight's headline: Dr. Who and Captain Picard Star in Hamlet!

Well, it's true. The Royal Shakespeare production has opened, with David Tennant (Doctor Who on the BBC) as Hamlet, and Patrick Stewart (formerly of

Star Trek: The Next Generation, but more recently the prize-winning lead in

Macbeth) as both Claudius, Hamlet's stepfather, and the Ghost of his father, the King who Claudius murdered.

"The hype, it seems, was justified," began the

Guardian's roundup of the reviews. Michael Billington, the Guardian's critic, one of the most eminent in the UK, wrote (according to this story)

that Tennant has no difficulty making the transition from the BBC's Time Lord to Shakespeare's Hamlet, a man "who could be bounded in a nutshell and count himself a king of infinite space". Indeed, Tennant - "active, athletic, immensely engaging" - is one of the funniest Hamlets Billington has ever seen, who goes on to say that, overall, it is "one of the most richly textured, best-acted versions of the play we have seen in years". The only thing that is missing is an insight into Hamlet's philosophical nature, something Billington partly attributes to director Gregory Doran's cuts to Shakespeare's longest play, resulting in some of "the most beautiful lines in all literature" being lost.

This was pretty much the consensus view: Tennant was very good but not (yet) great, and Patrick Stewart was brilliant. Another reviewer wrote that his performance as Claudius was the "strongest, scariest" he'd ever seen, "acting of the highest order." Others also mentioned the cuts in the text as too severe, resulting in more of a revenge drama.

Billington also

wrote of Tennant, "He is a fine Hamlet whose virtues, and occasional vices, are inseparable from the production itself...

This is a Hamlet of quicksilver intelligence, mimetic vigour and wild humour: one of the funniest I've ever seen. He parodies everyone he talks to, from the prattling Polonius to the verbally ornate Osric. After the play scene, he careers around the court sporting a crown at a tipsy angle. Yet, under the mad capriciousness, Tennant implies a filial rage and impetuous danger: the first half ends with Tennant poised with a dagger over the praying Claudius, crying: "And now I'll do it." Newcomers to the play might well believe he will. Tennant is an active, athletic, immensely engaging Hamlet. If there is any quality I miss, it is the character's philosophical nature, and here he is not helped by the production."

Hamlet is a defining role for an actor. As Canadian actor (and star of the TV series

Slings and Arrows) Paul Gross commented, actors are considered pre- or -post Hamlet. It's self-defining even for actors who never get to play the role. In their

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead DVD interviews, both Gary Oldman and Richard Dreyfus are wistful about missing their chances to play Hamlet--both felt even at that time that they were too old. Dreyfus held out some hope for being able to do a radio version, but even that seemed unlikely. Al Pacino (on his DVD called

Babblelonia) felt thwarted in doing any Shakespeare when he was young because he was too ethnic.

As for Tennant's good-but-not-great reviews, that could change: not only as this production continues, but as time goes by. I remember after seeing David Warner in the film

Morgan! I had high hopes for his

Hamlet (1965-67.) It was in England, and I never got a chance to see it, but I was dismayed at how dismissive the reviews were, at least the few I saw. Apparently, the reviews overall were mixed. So I was surprised to see, when reading about this new production, that

Warner's Hamlet is now considered so highly. Patrick Stewart

calls it the Hamlet of his generation, and Billington rates it in his top ten, of productions from 1958 to 2000. (Stewart later acted with Warner in a revival of Warner's

Hamlet, as well as in a notable episode of Next Gen.)

This new production also awakens intense envy of London theatregoers, who had the opportunity to see so many great actors take on this role, and for that matter the others in this play. And thanks in part to the wildly popular Doctor Who, but also to the place that theatre has in UK culture, this production is a real event--inspiring, among other things, in a newspaper

feature in which critics, actors and other theatrical celebs muse on their favorite Hamlets. Veteran critic Benedict Nightingale writes that he's seen at least 40.

Readers added their favorites in the comments to this article. Though I've seen Olivier, Branagh, Gibson, etc. in their film Hamlets, the only name actor I saw play the role on stage was Kevin Kline at the Public Theatre, and I wasn't terribly impressed.

My favorite Hamlet was my first, the inaugural production of the new arts center at Knox College, where I was a freshman. A student named Jim Eichelberger played Hamlet, and he was astonishing. He went on to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, was a lead actor at Trinity Rep in Providence before becoming a star of experimental theatre, as Ethyl Eichelberger. He appeared in a production of

The Threepenny Opera with Sting in the 80s. But he contracted AIDS, was apparently resistant to drugs of the time, and committed suicide in 1990--in fact, as I see his Wikipedia bio, on this very date, August 12.

Another production I liked a lot was one at the University of Pittsburgh, which had a summer Shakespeare festival, with performances in a kind of round stone castle called the Stephen Foster Memorial--very atmospheric for Shakespeare. A Canadian actor called Richard McMillan played Hamlet (I recognized him a few years ago in a small but substantive role in the movie,

The Day After Tomorrow, acting with the great British actor Ian Holm.) I remember that this production started as a kind of postmodern dress Hamlet, but as the action intensified, the actors were all in sober Elizabethan costume. McMillan started out playing Hamlet as a moody young rebel with John Lennon shades, perhaps an echo of David Warner's very 60s hero.

Also associated with the new

Hamlet, there was some controversy in England over celebrities possibly overwhelming Shakespearian productions. Director Jonathan Miller was critical (even though he's been known to use famous actors), but Michael

Billington defended the Tennant production. It also helps that both Tennant and Stewart were trained and worked in RSC productions. The tradition of going back and forth between theatre and TV and theatre and movies is much more established in England, and Billington finds that a little screen stardom may even improve stage confidence and performance.

But Hamlet isn't the only

Shakespeare in the News, not in England, oh no. Here's the breathless beginning to the Guardian

story:

A shiver of excitement rippled around the theatrical globe as news spread of some grubby red bricks uncovered in a muddy pit off a nondescript street in east London. Sir Ian McKellen will be making his way to New Inn Broadway in Shoreditch, one of many theatre luminaries impatient to see the site where his hero William Shakespeare learned his trade not just as a playwright but an actor.

It's The Theatre (that's what it was called) that's been lost for 400 years. Or anyway, part of its foundation--because the actual theatre was simply dismantled and transported to another location, where it became The Globe. It's believed to be the theatre where Shakespeare first acted, and where his first plays were performed.

Now that the site is known for sure, it can be properly excavated and the dimensions of The Theatre studied. Believed to have been built in 1576, it is where Shakespeare learned his craft. Its foundation was found by archeologists who had clues it might be there, while the site was being cleared for a new building: a new theatre, in fact.